Rebuild of Blossom

DATE: 2024-11-15This post presents updates to Blossom, the robot that I developed in grad school.

The current version of Blossom, with a new chevron cover1 and accessories: glasses for seeing; hearing aid for listening; name tag for communicating. Stereographic GIF courtesy of Cyril and the PIMSLO camera.

Blossom is an open-source robot platform for human-robot interaction (HRI) research that I developed during my PhD.

I’ve used Blossom for research in design, machine learning, and telepresence; others have made Blossoms for their own research purposes.

I have continued working on “rebuilding” the entire platform2: I redesigned the inner frame as a model kit, complete with Gunpla-inspired runners and instructions, and refactored the codebase as r0b0, a Python library for communicating between hardware peripherals and software applications.

In preparation to present Blossom at Maker Faire Coney Island, I refined the telepresence interface and enabled conversational interaction with a language model.

The new repository is available on GitHub and includes documentation for construction.

Plastic love

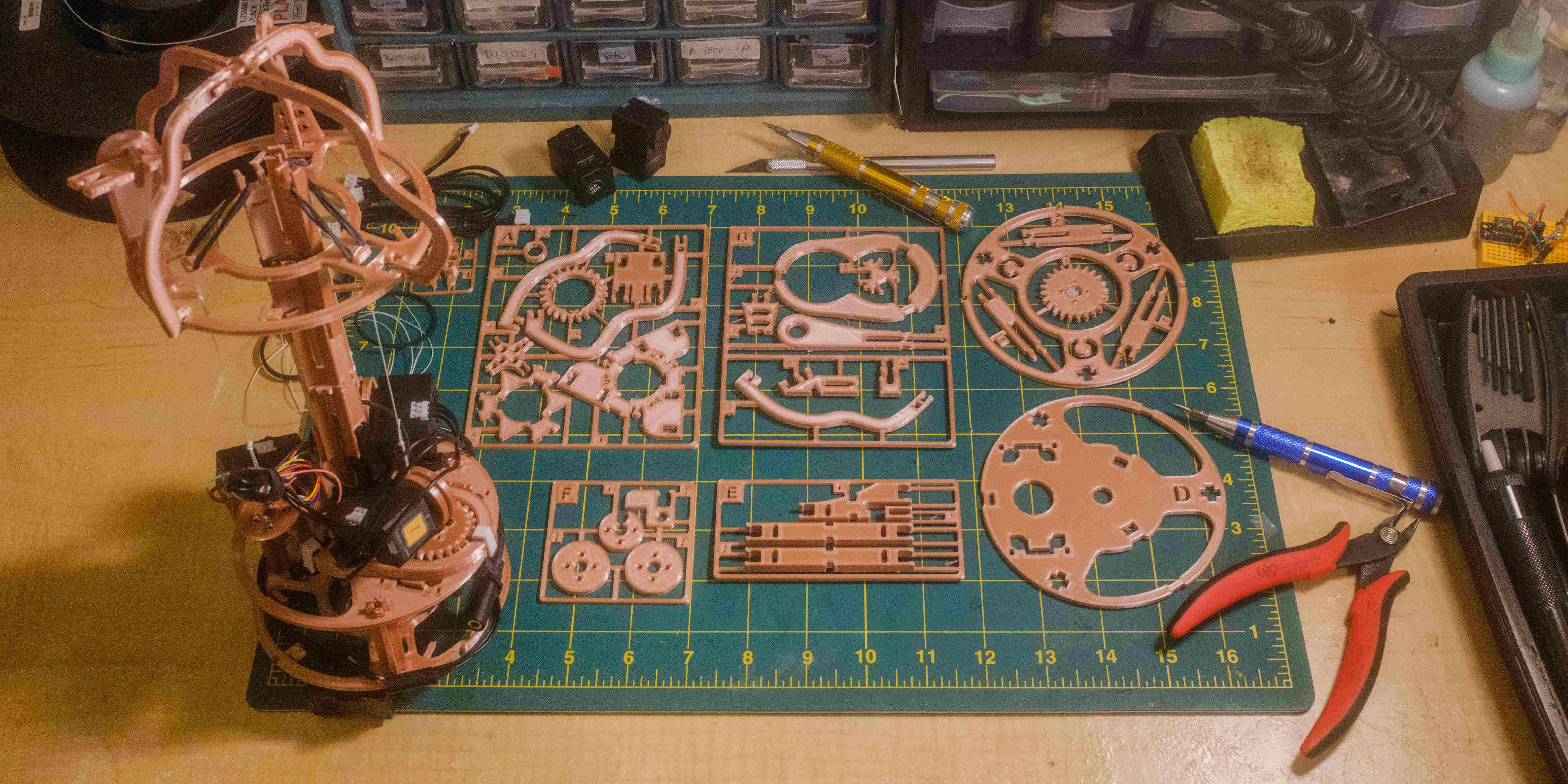

The redesigned inner frame and layout of parts. Some runners are repeated during construction: the completed model uses only one A and D runner, but two B and C runners, and three E and F runners.

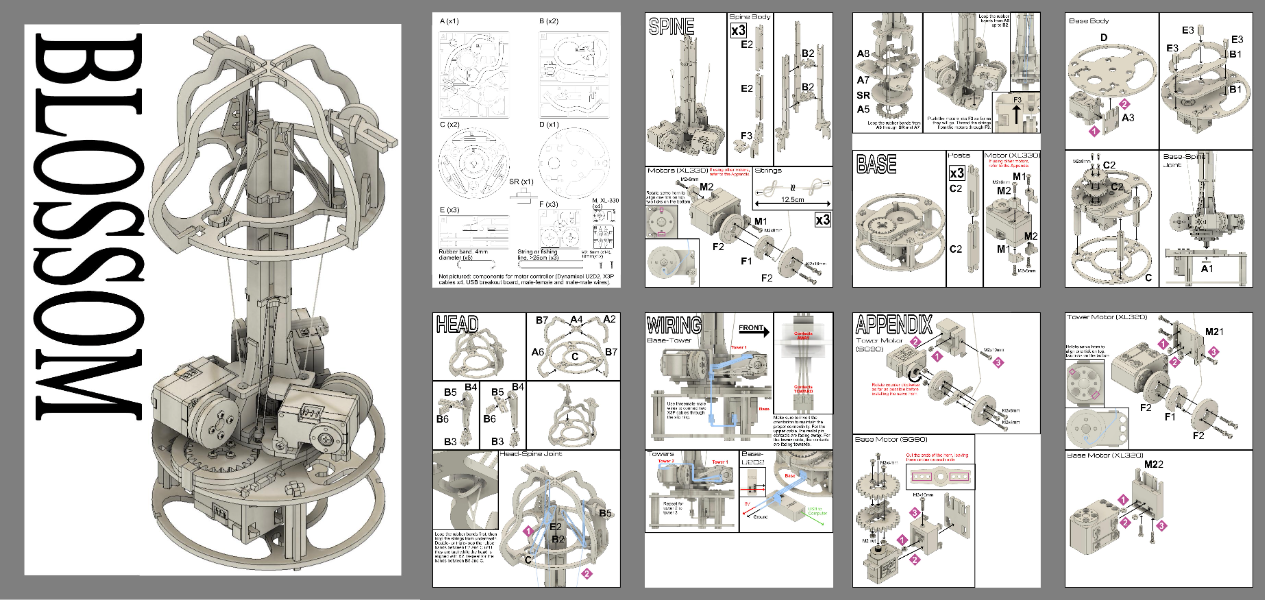

I have been rebuilding Blossom on-and-off since I finished grad school, though others in academia have also taken Blossom in different directions. Most notably, researchers at USC have forked the project for their own work. They simplified construction from the prior laser-cut wood version3 by combining parts into larger components for 3D printing. I went in the opposite direction, instead further decomposing the design into smaller parts as an homage to the robot model kits that first inspired me to make. The parts are still mostly flat — they can be either printed or laser cut from wood, though the tolerances would need adjusting — and can be printed individually or in “runners” like actual injection-molded model kits. The redesign improves modularity for customizability (e.g. one could shorten the robot by just using less of the spine parts, or enlarge the base by lengthening just one part), requires less hardware (only needing the screws included with the motors), and includes an instruction manual inspired by Gunpla manuals.4

The instruction manual with 3D illustrations instead of phone pictures.

The redesign also uses the newer Dynamixel XL-330 servos. Compared to the XL-320 used in prior versions, the XL-330 is smaller, easier to mount, and more fully featured. The XL-330 is capable of full 360º rotation through 512 revolutions with position tracking, whereas the XL-320 can only spin full revolutions in “wheel” mode without position feedback. Less excitingly, the XL-330 nominally operates at 5V, easily tapped from any USB power supply; the XL-320 nominally operates at 7.4V and is prone to burning out after extended undervoltaging at 5V.

The medium is the message-oriented middleware

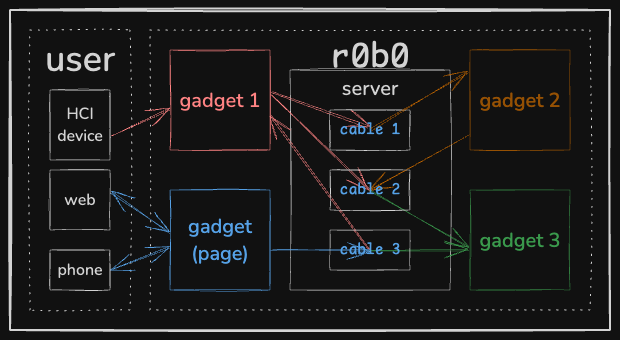

Software diagram of r0b0, showing the network of “gadgets” and “cables” that translate messages between them.

I have totally refactored the software from a series of slipshod scripts to an actual Python library.

This undertaking was equally requirements-driven and educational, as I wanted to architect a device networking tool that I can5 use for other projects and is lighter than ROS.

The result is r0b0, “an aconnect for anything.”

The tool is message-oriented middleware6 for connecting “gadgets” — hardware peripherals like motors or MIDI controllers and software applications like pygame or a camera driver or a server — through “cables” that translate messages between them.7

The library uses Flask-SocketIO to pass messages between the gadgets, which themselves are not explicitly aware of other gadgets in the network.

The gadgets comprising Blossom include motors, serial devices, language models, and web page servers for the control interface.

Old bot, new tricks

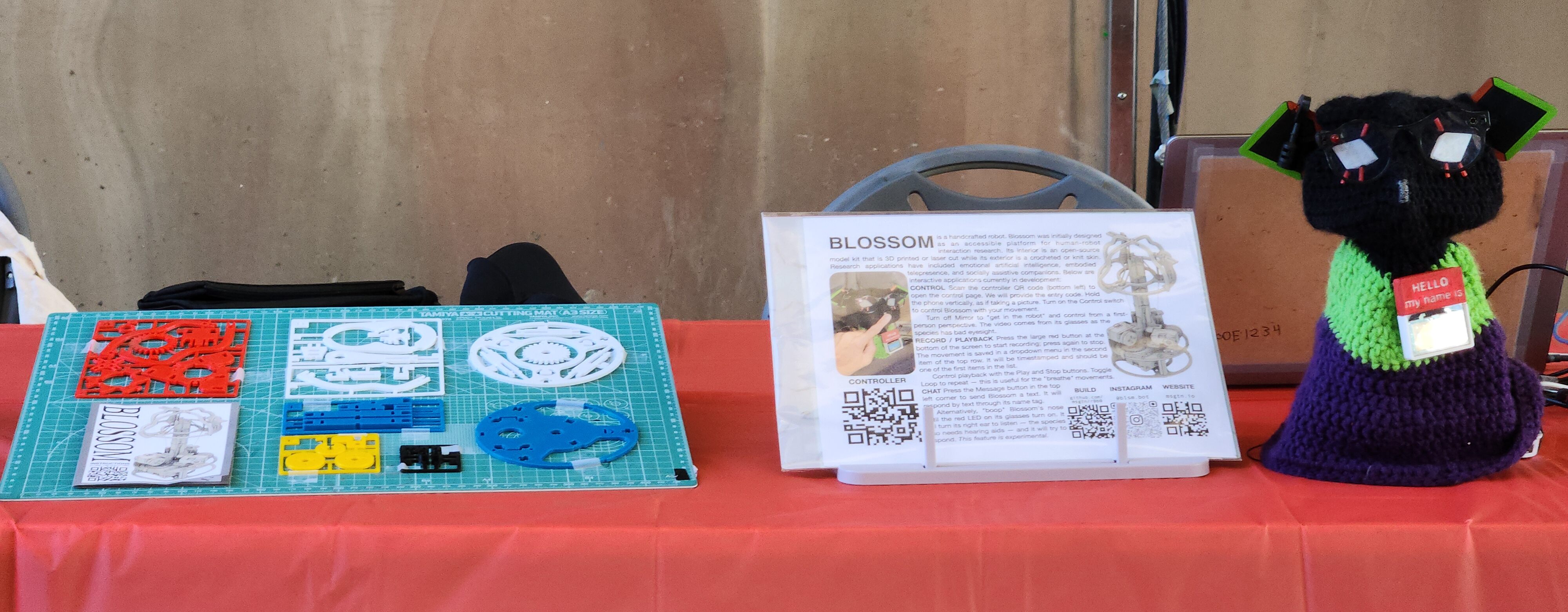

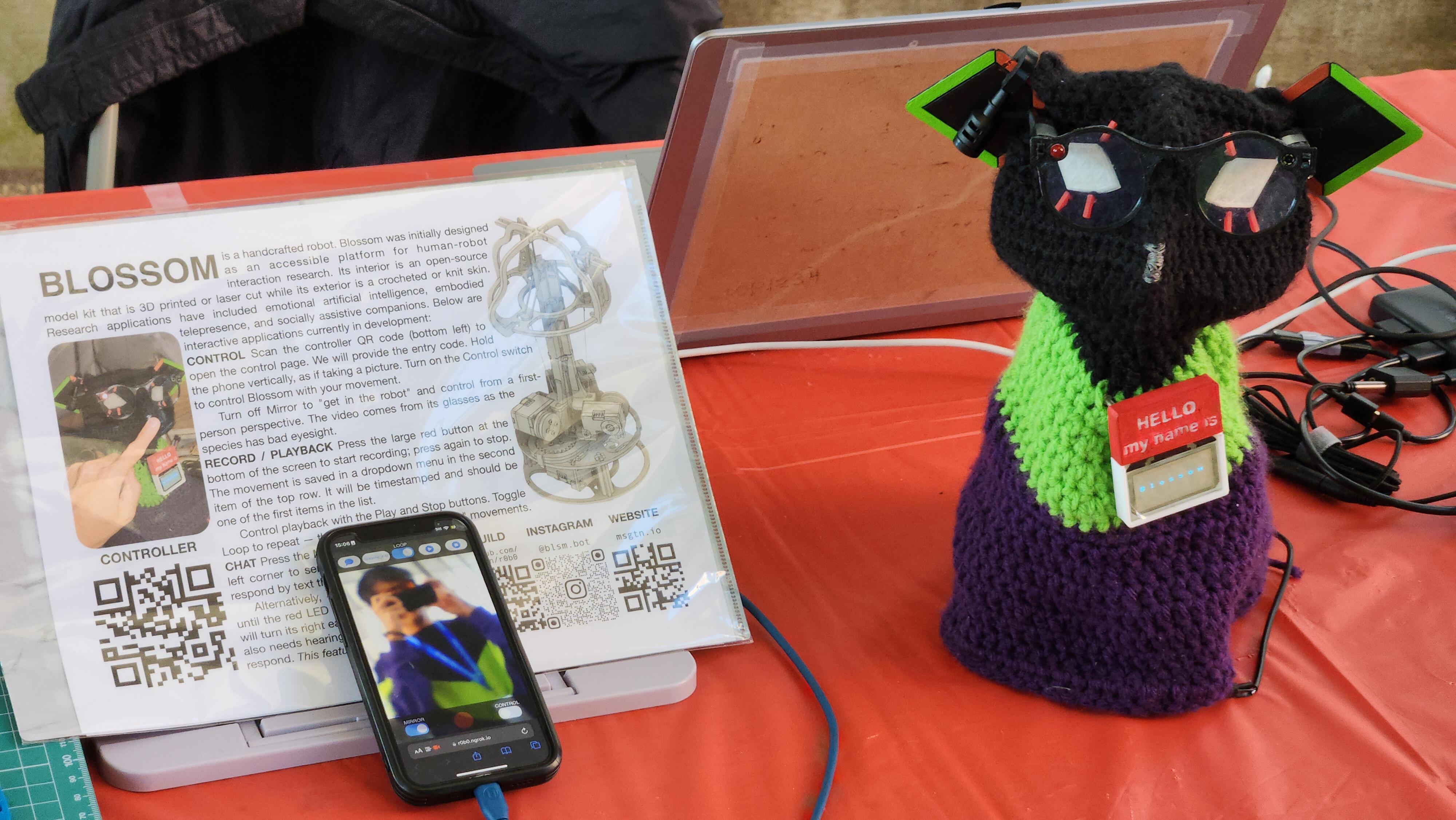

The exhibition setup at Maker Faire.

I took Blossom to Maker Faire Coney Island — my first “Make” event. In preparation, I refined the existing interaction of the motion-based mobile interface and added long-planned language model capabilities.

One of the interactions at Maker Faire: a girl dancing in front of Blossom while another attendee controls the robot.

Get in the robot

The main control method for the robot, at least in my versions, is a motion-based interface on a mobile device to control the robot’s head.

For the telepresence applications I researched,8 I enabled motion control using DeviceOrientation events and added a remote video feed from a camera in the robot’s head using WebRTC.

Users control the robot remotely through a mobile web page — no downloads required — that maps the orientation of the phone to the pose of the robot’s head and displays the video feed from the robot’s camera.

The implementation was sufficient for guided user evaluations but had many flaws: the mobile interface was messy and uninspired, and I haphazardly clipped the unwieldy camera to the ear in the absence of a proper mount.

Regarding the software interface, I redesigned the controller to resemble mobile camera interfaces. The video from the camera is “full bleed” across the whole screen, with control buttons on a lower toolbar. In place of the shutter button is a record button for recording a movement for later playback. The upper toolbar is primarily for playback of recorded movements: a user selects a movement to play or stop, with an optional toggle for looping. The upper toolbar also has a messaging button for communicating with the language model (described later).

The motion-based mobile interface inspired by mobile camera interfaces. The interface maps the orientation of the phone to the pose of the robot’s head and broadcasts a video feed from the robot’s camera. The bottom toolbar includes controls for the robot. The top toolbar includes controls for playback and texting a message to the robot’s language model.

Regarding the camera hardware, I designed fake glasses with an endoscope camera in the temple. I drew inspiration from Williams’ “All Robots are Disabled”, Joshi et al.’s work on accessories for robots, and new glasses-embedded cameras; what could robot accessories look like, and how could they communicate capability? The “lore” is that Blossoms, as a species, have poor eyesight and thus need glasses to see, just as humans would.9

A closeup of the robot’s new accessories, including the camera-enabled glasses, ear-mounted hearing aid, and capacitive nose “boop” sensor. On touching the nose to initiate a prompt to the language model, the red LED in the glasses lights up and Blossom turns its ear toward the user.

The shape of voice,

the shape of text

Human-robot interaction is a minority case where shoehorning using language models is actually sensible.

I created a r0b0 wrapper around the llm library to trigger prompts in two ways.

First, one can physically “boop” Blossom’s nose which is made of conductive thread.

The thread leads to a capacitive sensor on a Raspberry Pi Pico in the base; a red LED in the glasses opposite of the camera will indicate a sensed touch, and Blossom will turn and raise its ear towards the user to indicate that it’s listening.

Just like their bad eyesight, Blossoms have bad hearing and thus need a “hearing aid:” a small microphone clipped onto its ear.

A r0b0 speech-to-text module forwards the message to the language model.

Alternatively, one can text to Blossom through the mobile interface, which sends the message directly to the language model.

Texting through the interface skips the “listening” movements from the boop but is more robust.

For vocalizing, others have used text-to-speech to give Blossoms a voice, but human voices are dissonant against the robot’s design. One paper using Blossoms for meditation even found that adding a synthetic voice worsened the interaction.10 Playing to Blossom’s zoomorphic design, I used an Animal Crossing “animalese” generator for vocalizing the language model’s output through a speaker in the base. Because the sound is intentionally garbled, I created a name tag11 with a Pico-controlled transparent OLED to type out the response. The response also creates a motion curve to nod the front head motor in time with the vocalization and text. I did not spend much time tuning the language model, apart from crafting simple prompts for the robot’s identity (e.g. “you are a robot, not a language model”). This feature did not get much use at Maker Faire due to the loud open-air environment, but is still something that I am developing.

A demonstration of the language model feature. Blossom responds in garbled “animalese” as the name tag prints the text.

Once and future work

Scenes of interactions at Maker Faire. In the last frame, an attendee shows Blossom its own video feed, creating an infinite tunnel effect.

Maker Faire was a great time and reminded me of some of the highlights of grad school: the responses to the robot, especially from kids and other makers; the slow realization of how the system works; surmounting myriad technical issues to reach a stable demo. Most attendees were interested in the motion control, though a few held short conversations with the language model. It was inspiring to be around others who make not out of obligation, but because they choose to and express themselves through their work. Blossom was also voted Best in Show, thanks to the attendees who enjoyed the interaction. Next goals include:

- Set up the robot as a persistent telepresence device, one that friends or relatives can call into like a landline telephone.

- Explore language models for designing a character, with persistent memory and affective modulation. Representation engineering with control vectors to modulate outputs looks like an interesting approach, and is something I researched with autoencoders in prior work.

- Continue refining: the cables to all the peripherals are unwieldy; the expensive single-purpose U2D2 Dynamixel controller can be replaced by the cheap multi-use Pico and a Dynamixel MicroPython library; the codebase, as always, can be tidied up.

Blossom’s r0b0 repository is available on GitHub and includes documentation for its construction.

-

The first that I have actually crocheted myself. ↩

-

I think we all have an affinity with our projects, let alone when it’s a creature with a face and a name to whom you owe many opportunities. And I had many ideas I wanted to implement but couldn’t for being too orthogonal to research, i.e. not immediately publishable. ↩

-

The prior version was designed from laser cut wood for two reasons. First and practically, for quick iteration as laser cutting is much faster than 3D printing. Second and philosophically, as a “statement”12 about designing a “transient” robot from materials that will age in contrast to the plastic and metal typically used for machines. But laser cutting and wood are much less accessible than 3D printers that are only getting better and cheaper, which opposed the project’s theme of accessibility. ↩

-

Thanks to Sean for finding the exact fonts used in the Real Grade Wing Gundam instruction manual that served as a reference. ↩

-

In writing this, I kept accidentally typing “medium” in place of “message.” ↩

-

I was dabbling with hardware synthesizers at the time I decided to refactor the codebase. I wanted to emulate the interconnectivity of instruments united by the standards of MIDI and even the simple 3.5mm audio jack. ↩

-

Which I started at the end of 2019, just in time to be of relevance. ↩

-

As a former owner of several hamsters, the rodents that Blossom resembles have poor eyesight anyways. ↩

-

“Evaluating and Personalizing User-Perceived Quality of Text-to-Speech Voices for Delivering Mindfulness Meditation with Different Physical Embodiments”, Section 5.2: “We found that the feminine [text-to-speech (TTS)] voice had a significantly lower rating in the socially assistive robot condition than in the No Agent and conversational agent conditions. This is somewhat surprising, because we expected the computer-synthesized TTS voice to align better with the robot’s physical embodiment than the other voice options… This suggests that the alignment between the robot embodiment and voice may help to remind and amplify the user’s dislike of the artificial sound of a TTS voice.” ↩

-

I planned to use a larger display and mimic an Etch-A-Sketch with motors to fake the already-fake letter-by-letter output of the language model. Still considering this. ↩