Leica MPi

DATE: 2023-04-20or How I Learned to Stop Gear Acquisition Syndrome and Build My Own (Post-)Digital Leica

The Leica MPi: a Leica M2 with a Raspberry Pi-powered digital sensor.Featured on PetaPixel, Leica Rumors, Hackaday, hackster.io, Tom’s Hardware, and Raspberry Pi.

I introduce the Leica MPi (pronounced either ‘em-pa-i,’ a portmanteau of the Leica ‘M’ and the Raspberry ‘Pi,’ or letter-by-letter as ‘em-pi-a-i,’ like the Nintendo ‘DSi’): a film Leica M2 with a digital back based on a Raspberry Pi Zero W microcomputer and a 12-megapixel 1/2.3” camera module. The MPi preserves the key affordances of the base Leica M2, specifically its rangefinder focusing and mechanical shutter. The system is non-destructive: the digital back swaps in place of the existing film door and pressure plate, enabling reversibility. Assuming component availability at MSRP, the total cost sums up to less than $100 USD, or ~1% the cost of the newest digital Leica. The project combines the maintainability of an analog film camera with the convenience of a digital recording medium into a (post-)digital system designed for maintainability and extensibility.

Nakano Broadway, 2023

Related Works

Others have created similar digital backs for film cameras. Becca Farsace and Malcolm-Jay gutted film cameras to embed the same camera module, though the film cameras are essentially aesthetic housings for the camera internals. befinitiv created a digital back for a single-lens reflex film camera (Cosina Hi-Lite) using a Raspberry Pi. Though the entire assembly fits inside the camera, the implementation requires persistent remote access to view the camera’s output and uses an older, smaller 1/4” Pi sensor that yields a crop factor over 10x.

Some design goals for this project were:

- Preservation of the affordances of the base film camera, i.e. minimize the difference between the use with and without the digital back,

- Usability not dissimilar to modern digital cameras,

- Non-invasiveness and reversibility to the original camera, and

- Maintainability and extensibility for eventual open sourcing.

Implementation

Hardware

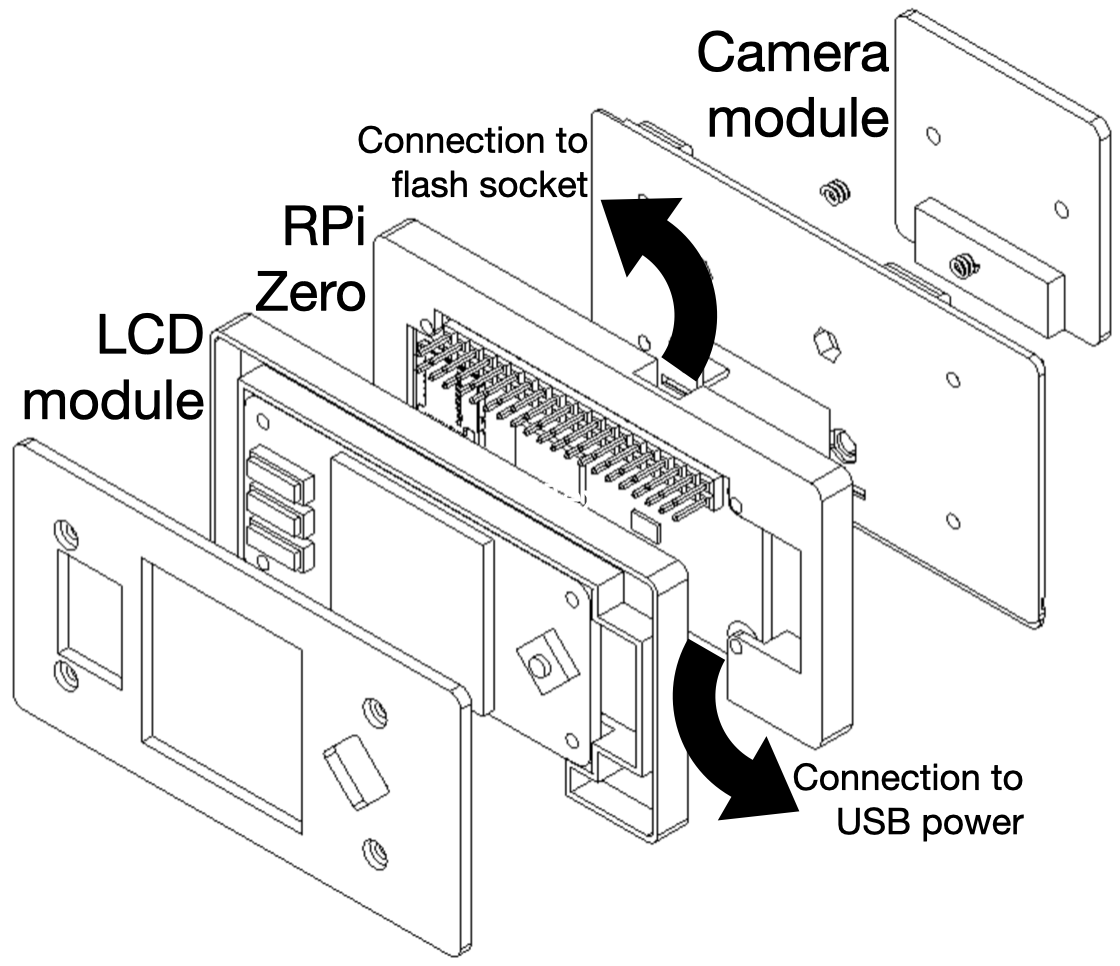

Exploded view of the digital back.

The camera is a film Leica M2 dating back to 1966. The sensor components consist of:

- Raspberry Pi Zero W ($15),

- Raspberry Pi HQ camera module ($50), and

- WaveShare 1.3” LCD module with three buttons and four-way directional pad ($15)

I designed the 3D-printed enclosure in Fusion 360. The camera module is based on the Sony IMX477 1/2.3” sensor, which yields a 5.5x crop factor (e.g. a 10mm lens is equivalent to ~55mm on a 35mm full-frame camera). Due to tight tolerances and mechanical interference with the Leica’s shutter curtain, I removed the module’s C-mount attachment and anti-aliasing filter and filed down the top edge of the sensor board.

Rangefinder

The rangefinder focusing system is preserved by matching the sensor position to the original film plane. The sensor is mounted on spring-adjusted screws for calibrating the sensor’s flange distance. I calibrated the sensor empirically by focusing, taking a picture, and making adjustments until the focus was acceptably sharp. Focus that is farther than expected indicates that the sensor is too close to the lens: the flange distance must be increased by tightening the sensor screw mount towards the rear of the camera; the instructions are reversed for close focus.

Shutter

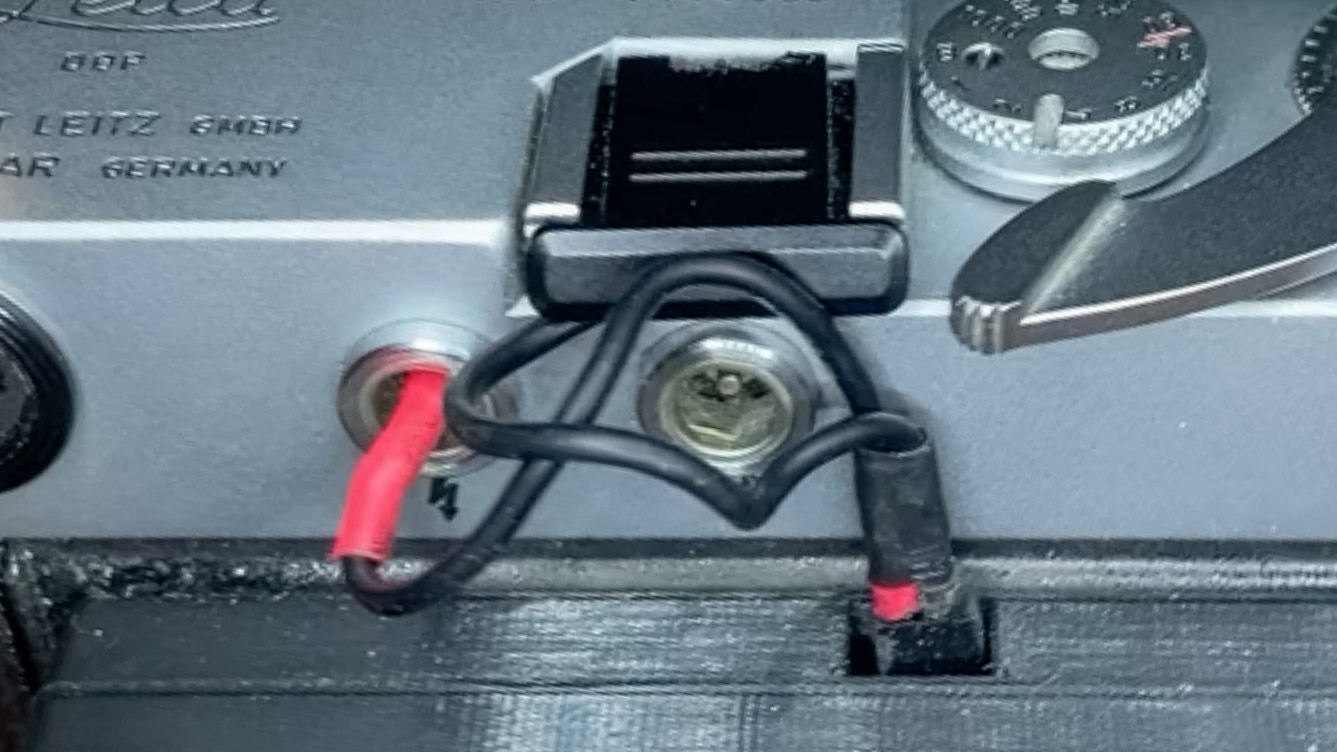

The cables for synchronizing the Leica’s mechanical shutter to the Pi’s electronic shutter. Both wires act as ends of a button input to a GPIO pin: black to ground (e.g. the camera’s metal body) and red to the flash sync socket’s center pin. Pressing the shutter button closes this circuit.

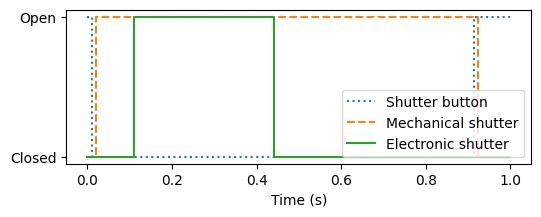

Temporal visualization of an exposure recorded by the electronic shutter. The closing of the shutter button both opens the mechanical shutter and closes the flash sync circuit. The closing of the flash sync circuit sends a signal to the Pi to begin an exposure with the electronic shutter.

The mechanical shutter is coupled to the Pi’s electronic shutter. Pressing the shutter button closes the circuit between the flash sync socket center pin and ground (e.g. any bare metal on the body; I used the cold shoe as a contact point). The mechanical shutter acts as a button input to one of the Pi’s GPIO pins and sends a software signal to begin an exposure with the electronic shutter. Due to software-induced lag between the opening of the mechanical shutter and triggering of the electronic shutter, the mechanical shutter stays open in ‘Bulb’ mode while the electronic shutter controls exposure. The four-way directional pad on the LCD screen module selects the shutter speed in two-stop increments: 1/1000, 1/250, 1/60, and 1/15 clockwise from right.

The system is powered by micro USB power supply to the Pi. I used an Anker 511 power bank with integrated wall plugs for ease of recharging. Because the battery does not need to power any motors as in a conventional digital camera, the battery rating is independent of shot count and is enough to power the system for several hours.

Software

The software is a refined evolution of the control framework that I wrote for Blossom, the robot that I developed during my PhD.

At its base, the framework is a communication wrapper between various hardware and software ‘gadgets:’ motors, MIDI musical instruments, web servers, and, for this application, buttons and cameras.

In this implementation, pressing buttons (i.e. the mechanical shutter button, the LCD module’s directional pad) sends event signals to the camera driver.

The MPi broadcasts a WiFi network for remote networking via ssh or VNC and wireless file transfer through smb for near-instant image review on a laptop (i.e. during development) or mobile device (i.e. during deployment).

Deployment and Photos

I first used the MPi on my April 2023 trip to Japan. I used the Voigtlander 12mm f5.6, which translates to ~60mm with the camera module’s crop factor. A software bug left the shutter speeds slower by a magnitude, e.g. what I thought I had programmed as 1/1000 was actually 1/100. As a result, I had to take most outdoor photos at f16-22, which brought out the imperfections and scratches on the sensor that accumulated from developing the prototype. Apart from cleaning these artifacts — tantamount to digitally cleaning dirt and scratches in film scans — and exposure and color correction, these images are unedited.

Due to the removal of the anti-aliasing filter, photos under natural light render with an extremely magenta tint.

Photos under artificial lighting (e.g. shops, street lamps, subways) may be corrected with white balancing.

Mixed lighting conditions can produce interesting renditions.

Discussion, or ‘Why?’

The following is half-baked pseudo-academic navel gazing.

Apart from making for making’s sake, I wanted to explore the critical design of a post-digital camera. Critical design ‘uses speculative design proposals to challenge narrow assumptions, preconceptions and givens about the role products play in everyday life.’ Post-digital is an aesthetic that spans rejection of the promised perfection of digital technologies (e.g. negative valuation of ‘clinical’ lens sharpness or ‘crystal-clear’ audio fidelity), the blending of digital and analog mediums and affordances, the foregrounding of creative processes over produced creations, and political desires for technological agency. By designing a post-digital system that integrates a digital recording medium within a completely analog mechanical film camera, I wanted to critique the unsustainability of both film and digital photographic practice.

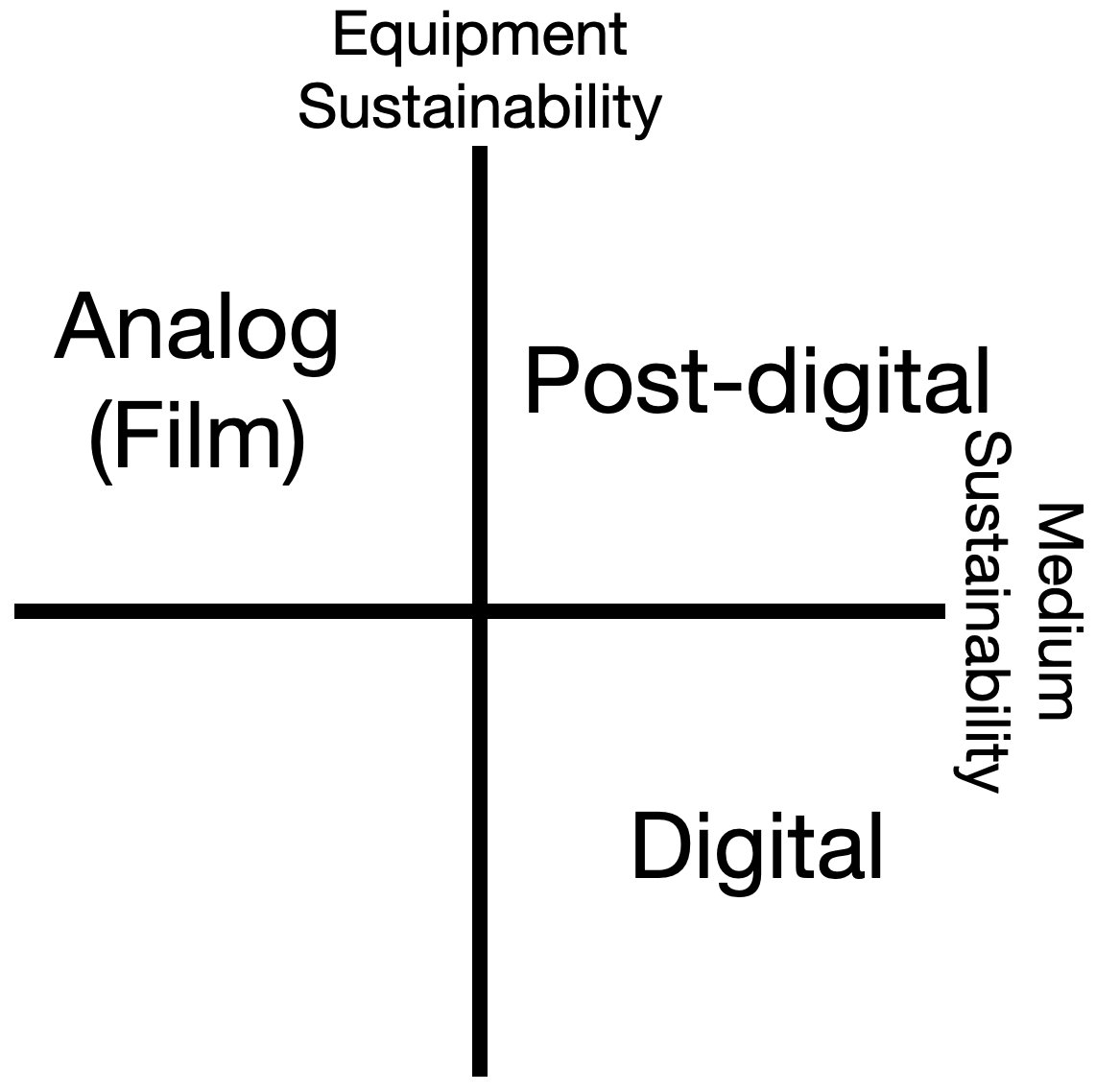

Qualitative comparison of analog, digital, and a proposed post-digital photographic practice along the axes of medium and equipment sustainability.

Analog photography has experienced a recent revival. Film photographers find appeal in the process (e.g. deliberation of each frame and physical handling of film materials compared to the easy immediacy of digital), product (e.g. filmic tonal and color renditions that are oft-simulated by digital systems), and nostalgia for physicality, unrememebered or not.

‘You’re shooting film?! In this economy?!’

The analog medium of film is unsustainable, both individually and communally. Regarding individual unsustainability, film prices for popular stocks (e.g. Kodak’s Portra and Tri-X) have more than doubled — in some cases, tripled — since I began using film in 2016. Film stocks are also persistently at risk of discontinuation. Regarding communal unsustainability, film materials and processing chemicals require special handling and treatment practices. Though literature on the treatment of photographic waste indicates little or no adverse environmental effects from processing chemicals, this assumes appropriate handling by institutions, i.e. legally regulated film processing labs. Though the Stockholm Water Authority attributed the city’s halving of silver halide pollution to the closing of local film development labs, this dropoff preceded the recent film revival, which ushered the growth of smaller local developing shops or individual amateurs who may not abide by the former stringency of film handling. However, analog equipment is relatively sustainable by virtue of maintainability. Many analog cameras are at least partially functional despite non-working electronics. The Leica M2, M3, and M4 contain no in-built electronics, and the M5 and M6 are operable even without batteries for their built-in light meters. The mechanical innards are serviceable — even by self-taught amateurs — given the availability or manufacturability of equivalent hardware (e.g. springs, levers). Many used camera shops — especially in Japan, where it seems like the new complements the old without supplanting it, unlike in the West — carry preloved and perfectly functional analog cameras that deserve preservation through prolonged use.

Digital Leicas cost more than many preloved classic automobiles.

Conversely, the digital medium of electronic sensors is sustainable and repeatable, with sensors and shutters rated for hundreds of thousands of actuations. However, in the long-term, digital equipment is unsustainable as consumable commercial gadgets. Because of the tight integration of complex electromechanical systems, malfunctions of singular subsystems in digital cameras (e.g. damaged sensors or faulty shutters) result in either costly manufacturer-locked repairs or total discard of the camera. The dependence on services beyond individual means both strips users of technological agency and adds to the global toll of e-waste.

The Leica MPi combines the maintainability of the analog Leica M2 with the convenience of a digital recording medium. The system is post-digital in not just its apparent combination of analog and digital elements, but also in its promotion of agency over its constituent technologies. Similar to the Right to Repair and Maker movements, this design philosophy appeals to a desire to be ‘master of one’s own stuff.’

Conclusion

I presented the Leica MPi, a post-digital camera based on the analog Leica M2 film camera equipped with a Raspberry Pi-based digital sensor as a recording medium. The MPi is usable as a normal camera and its modifications are reversible to the original base camera. I plan to continue developing this project with the goal of open-sourcing the design for the collaborative preservation of analog cameras through (post-)digital technologies.